Soil nutrient management is a vital part of regenerative farming and applying climate-smart practices can…

Fit Or Fat?

Certified Animal Welfare Approved by AGW standards require farmers and ranchers to maintain all animals at a Body Condition Score of 2 or more, while breeding animals must not exceed a score of 4 (both on a scale of 1 to 5). But what does this mean—and how can Body Condition Scoring be used as a livestock management tool?

What is Body Condition Scoring?

Body Condition Score (BCS) is a measure of an animal’s energy reserves (or fat reserves) and muscularity. Animals can lay down fat at times when feed is plentiful and mobilize it when the available feed does not meet their nutritional demands. The aim is not to keep BCS at exactly the same level all the time, as some variation in energy reserves will naturally occur during the production cycle, but to maintain the BCS within expected limits—and to avoid extremes. Although the best live weight for a cow, sheep, goat or pig will vary depending on its breed or age, the optimum BCS is the same for all, making it a useful monitoring tool.

BCS can be used as a measure for individual animals, as well as an indicator of overall herd or flock condition. If there is a wide range of condition scores within the herd or flock—or numerous animals at either the lowest or highest extreme —a whole herd/flock review of nutrition, health and management will be needed.

BCS and fertility

BCS offers a useful indication of an animal’s nutritional and health status, so it makes sense that animals with poor BCS will suffer slower growth rates and greater susceptibility to disease or parasite problems. However, BCS is also useful for assessing and predicting fertility.

Research shows that animals with a BCS of less than 2 have little spare energy reserves and are less likely to get pregnant. If they do get pregnant, they are more likely to lose the pregnancy or produce offspring with low birth-weights, and therefore a lower chance of survival. Lactation will also be poor. Similarly, animals with a BCS of 4 or more are also less likely to get pregnant—and if they are pregnant during the time their BCS increases to this level, the developing calf, lamb(s), kid(s) or piglets can grow so large the mother has trouble giving birth. Animals with high BCS can also suffer from leg problems and lameness from the additional stress of their weight and fat levels on their feet and limbs.

Aside from affecting health and welfare, failure to meet expected BCS levels can be costly due to poor animal performance, the extra costs associated with providing veterinary care and wasted money spent on unnecessary feed.

What’s involved?

BCS is a simple, practical management tool. With practice, it is possible to assess animals quickly and easily. Monitoring BCS allows early management intervention to either start or stop supplemental feeding, treat animals for parasites and other health problems, change pasture rotation and any other actions to keep animals in the right condition.

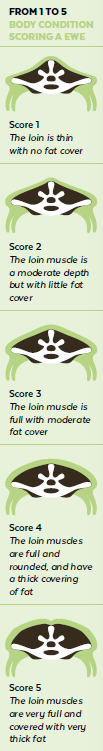

BCS for pigs, goats and sheep is generally assessed on a scale of 1-to-5, while cattle are assessed on either a 1-to-5 or a 1-to-9 scale. (There is at least one 1-to-9 scale for goats, too.) Several guides are available with example scales and photographs of animals at different scores (see ‘Further Information,’ below).

While a visual assessment can provide a rough idea of the BCS for cattle or pigs, this is clearly not an option with wool sheep. The most accurate way to carry out BCS for all species is with a combination of visual and physical assessment.

When to carry out BCS

Each type of animal has specific areas you should look at and feel by applying gentle pressure to establish how much muscle and fat surrounds the bones. For cattle, key areas include the tail head, ribs and loin areas; for sows, the backbone and hips; for sheep and goats, the main area is the backbone in the loin area behind the last rib. Depending on species, additional points, such as the shoulders, the ribs and the hip bones, can also be assessed to improve the accuracy of the score. Carrying out BCS at key times in the production cycle, such as birthing, weaning and service, will provide a good indication of overall herd or flock condition, particularly at these critical periods. Fortunately, this usually coincides with times when animals are being handled anyway, allowing you to integrate BCS with other management procedures. The key is to get an idea of what the optimum BCS levels are for the different production stages —and to be alert to those animals that fall outside these norms.

Remember: if all you do is look for individual animals that are thinner (or fatter) than their herd mates, the overall herd condition score could be going up or down without you noticing. You will need to assess a reasonable proportion of the herd or flock to really know what is going on.

What if the BCS is too high or too low?

If you find animals at the extremes of body condition levels, it is usually best to temporarily remove them from the herd or flock for special treatment. Never try to change body condition score too rapidly, as sudden changes in feed levels can lead to further problems. But by incorporating regular BCS assessments into your management practices, you should find in the future you only need to tweak nutrition to allow condition to return to optimum levels.

AssureWel

-

-

-

- BCS for beef cattle, dairy cattle, sheep and pigs. See assurewel.org

-

-

Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

-

-

-

- BCS for sheep (1-to-5 scale) and other species. Visit agric.gov.ab.ca and search “body condition”

-

-

American Institute for Goat Research

-

-

-

- BCS factsheet for goats (1-to-5 scale). Visit luresext.edu and select ‘library’

-

-

Canadian Pork Producers BCS for sows

-

-

-

- (1-to-5 scale); Animal Care Assessment manual (appendix 10). Visit cqa-aqc.com

-

-

Mississippi State University Extension

-

-

-

- BCS for cattle (1-to-9 scale). Visit extension.msstate.edu and search “body condition”

-

-

NC State Cooperative Extension

-

-

-

- BCS for goats (1-to-9 scale). Visit ces.ncsu.edu and search “body condition”

-

-

Ontario Ministry of Agriculture Food and Rural Affairs

-

-

-

- BCS for dairy cattle (1-to-5 scale) and other species. Visit omafra.gov. on.ca and search “body condition”

-

-

Author: Anna Heaton, Lead Technical Advisor with A Greener World

Originally published in the Winter 2018 issue of AGW’s Sustainable Farming magazine.