Market research shows that today’s consumers are increasingly interested in knowing where their food comes…

Getting A Handle On The Herd

Depending on the circumstance and the animals, getting cattle to do what you want can be very easy, very difficult or nearly impossible.

I grew up working cattle on my family’s ranch, TK Ranch in Alberta, using horses and dogs to help get the job done—a practice we continue to this day. When I was a kid in the 1960s, however, horses were broke, cattle were chased, and dogs and kids tried to help (but mostly just learned to stay out of the way). Back then, if livestock were not cooperating it was standard practice to show them—in no uncertain terms—who was the boss. I don’t recall any other consideration for doing anything different.

A high-stress environment

One of my early memories was going with my Mom down a back road on a dark rainy night to check on my Dad. I was about seven. He was out on horseback bringing a heifer back to the yard. He was riding a big black gelding named Rowdy. I remember my Mom driving very slowly and Dad charging out of the darkness up to the driver’s window. His slicker was shining from the rain and Rowdy was all lathered up. Both Rowdy and my Dad had the same wild look in their eyes. Dad was mad at this heifer for jumping fences to get away from horse and rider, and he wasn’t going to let her get away with it. That was usually the way with my Dad: he had a short temper when it came to working cattle and he was mad more often than not.

Our own worst enemy

Handling cattle can be challenging, frustrating and even maddening. It isn’t always a walk in the park. Some cattle are much more nervous than others and poor disposition can make it difficult if they run away as soon as they see you. An animal, or a herd of animals, consumed by fear is very difficult to control.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, extremely docile and tame cattle that totally ignore you can be equally impossible to move. They truly don’t care what you are asking them to do and some will even get obstinate.

There are also situations where you are asking your cattle to do something new; or where they are faced with novel obstacles they aren’t comfortable with, like crossing asphalt, bridges or railway tracks that makes moving them difficult.

In addition to the above, us humans also have a part to play. What I have learned in handling livestock over the last 50 years is that we can truly be our own worst enemies. It isn’t that we lack the virtues of patience, compassion, understanding and good will (though there is variation in that regard!). The biggest obstacles we face are our impulses around cattle. The things we do without thinking, without conscious awareness, that result in us being at the wrong place, pressuring at the wrong time and in the wrong direction, and either over pressuring or under pressuring relative to what the animal is telling us.

Counterproductive impulses

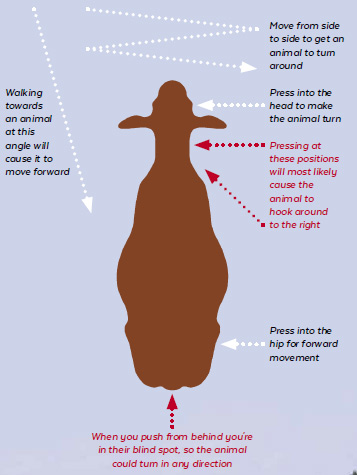

For example, people often think if they get directly behind a beef animal it will move forward. Yet cattle have peripheral vision: they have a blind spot directly in front of and behind them. When an animal can’t see what you are doing they will often stop and hook around to look. When you don’t understand this biological fact then it’s not unreasonable to think the animal is being difficult when they turn around instead of going forward. Once you understand this and adjust your position to being out from the hip instead of directly behind, then your ability to control that animal’s direction changes dramatically for the better. In short, we need to understand and address our counterproductive impulses when working cattle so that we can start to get out of our own way.

Some of you may protest upon reading this. I can hear you assuring me that your cows come when they’re called; that they willingly go through gates that you open when rewarded with fresh green grass or with the right feed in a bucket or on a tractor. I agree: those tactics can and do work.

What I ask you to recall, however, are the instances where no matter how sweet the feed, how green the grass or how lovely your voice that your cows refused to do what you asked. The times when they wouldn’t cross the asphalt or go into the corrals. Or when your bull refused to leave the neighbor’s cows. Or when a cow wouldn’t go onto the trailer or truck, or into the barn. Or when she lost track of her calf and ran back.

What behavior did you resort to in order to get the job done? I expect you resorted to what you were attempting to avoid by leading them: arm waving, whistling, hissing, possibly yelling, use of a cane or a whip, running, chasing and so on. Sound familiar?

Trust and respect

The happy medium between wild cattle and excessively tame cattle are manageable cattle. Cattle that respect you enough to yield their position to you. That trust you enough to respond in a relaxed walk in a calm trusting manner.

You can move manageable cattle where and when you want using your movement and your position to create the right pressure at the right place at the right time. This is what effective herding or driving is all about. Once you learn these techniques you can calm wild cattle over time so they trust you enough that you can herd them under control. You can also get super tame cattle to respect you enough to be able to get them to go where you ask. An effective working relationship with cattle is built on trust and respect and they are two sides of the same coin. Without a balance between trust and respect, moving a herd or individual animals will always be more challenging.

A working relationship

The question for the cattle industry isn’t whether the job gets done, because it always gets done, day in and day out. The question is how the job gets done.

At the end of the day is everyone still in one piece? Was human and/or animal safety and welfare compromised at any stage? Are we all still talking to each other? The running joke in cattle circles is that the best test of a future relationship is to have the happy couple work livestock together. If the couple is still talking—and like each other—afterwards, it’s a positive sign the relationship will work. I remember my Mom and us kids going back to the house in tears on many occasions; this seems to be a universal experience on family farms across North America. Not to mention that, as kids, we all knew the corrals were a great place to hear all sorts of colorful language!

After working livestock, it’s also good to reflect on whether there are broken boards to replace, wires to mend, gates to fix or vehicles to repair. Most importantly: at the end of the day are the cattle calm and relaxed and prepared to do the whole thing over again? Or do they trust you even less and want to keep you at an even greater distance? All food for thought.

Low stress meat

For those of us who direct market beef, ensuring our cattle meet their end in a calm, unaffected state is important on a number of levels. This requires that the animals be sorted, loaded, hauled, unloaded, penned and, when the time comes, be quietly walked into the stun box.

How they respond to this handling pressure will be the sum of all of their past handling experiences. If an animal is upset and its final moments are filled with agitation and fear, then all of the time and effort we have invested into animal welfare, right back to its birth, will be at risk of being wasted. Meat quality is directly related to stress: just ask any seasoned hunter and they will tell you that a clean kill results in the highest quality meat. We all care about our animals or we wouldn’t be in this business. Knowing they had a good last day because they were calm and quiet makes the whole process more digestible, too.

It’s easy to blame the cattle when things go awry. It’s easy to lose our patience and get mad when we face time constraints and are pressured to get finished. But for all the lost tempers and foul language, I guarantee that not one lick of it actually helped to get the job done. Good livestock handling starts with us and in the final analysis we must take responsibility for the outcomes or nothing will ever change.

Further information

Dylan Biggs offers regular practical seminars on low-stress livestock handling, including: introductory one-day seminars; intensive two- day cattle handling clinics; advanced cattle handling clinics; and custom cattle handling clinics. Find out more at dylanbiggs.com or call 1-888-857-2624. Watch Dylan in practice in a Canadian Centre for Health & Safety in Agriculture video: youtube.com/watch?v=45jAC5PEqTI

Dylan and Colleen Biggs raise Certified Grassfed by AGW beef cattle and sheep and Certified Animal Welfare Approved by AGW pigs at TK Ranch in Alberta.

Like you and I, cattle have their own personal space. A flight zone can be defined as the space surrounding an individual animal or a herd that, when penetrated, will cause an attempt to re-establish a comfortable distance from the intruder. Flight zones are not static; they will vary in size and shape due to a number of environmental conditions and circumstances. It is important to realize that the size of flight zones can change depending on the handling. You can shrink the flight zones of nervous cattle or increase the flight zones of quiet cattle that don’t want to move.

Low stress livestock handling is based upon strategic pressuring of the flight zone of individual animals or a herd. Ideally, a handler will never penetrate the flight zone so aggressively or so deep that the animals panic and take flight. Rather it is a process of applying and releasing pressure on the flight zone edge in a manner that gets the response you want. Pressure is equal to proximity, speed and body language.

Don’t confuse speed and body language. Remember: body language reflects your emotional state. You can be moving very quickly and yet still be calm and confident and you will get a totally different response than someone else moving at the same speed that is frustrated and angry. To make this work you need to develop a feel for the flight zone and an understanding of herding dynamics so you can be in the right place at the right time in the right manner. Having a feel for the flight zone will allow you to finesse the flight zones using your movement and your position to get the cattle to calmly and quietly go where you are asking.