One of the key attractions of our Certified Regenerative by AGW program is its practical…

A Pesky Problem

Through consistent observation, you always noticed which herd members were more susceptible to internal and external parasites. Fecal sampling helped you identify a few silent carriers: heavily infested animals spreading parasites on your pastures even though they showed no visible signs of disease. Over time you selected only disease-free, low-burden stock for breeding. Today, your animals graze diverse pastures replete with a variety of bioactive forages. Dung beetles thrive, dispersing manure piles and destroying many eggs, while predatory insects devour any fly larvae that manage to hatch. Of course, parasites are still present on your farm, but you understand their particular life cycles, move animals before they can re-infect themselves, and rest pastures or graze non-susceptible species such that the majority of parasites die before they ever find a victim.

If the above describes your farming operation, congratulations! The chances are you have little need for this article … But if seasonal ponds recently emerged in your well-drained grassland … if that doe with perpetually high fecal egg counts happens to be your best milker … if recent fires, floods or lease modifications caused you to group more animals in a smaller area … then you might benefit from additional strategies to manage parasites.

Applied Terrain Theory: Pasture

Exposure to parasites occurs for a variety of reasons. Most internal parasites arrive on your farm via infected livestock or wildlife, so maintaining a closed herd or screening new arrivals can help keep your pastures clean.

Snails and slugs act as intermediate hosts for some parasites; wet conditions favor these mollusks, but vegetation or gravel can act as a barrier to help exclude them. Environment also plays a role in risks related to external parasites. For example, woodland grazing increases exposure to ticks. If local wildlife are known to carry a specific worm, deterrents such as guardian animals or double fence lines can reduce their contact with your herd.

Dung beetles, earthworms, parasitic wasps and poultry are some of the most effective and economical tools to inhibit parasites on range areas. Dung beetles break up manure piles, damaging or desiccating eggs. Along with earthworms, they move manure into the soil and prevent many hatched larvae from returning to the surface. One interesting study assessed the impact of dung beetles when calves followed infested adults. Without any other intervention, calves in pastures with reduced dung beetle populations had nine times as many roundworms as those in pastures with more dung beetles. That’s a huge difference! If you’re among the large percentage of U.S. farmers who have recently considered building an ark, note that heavy rainfall can temporarily override dung beetle benefits.

Applied Terrain Theory: Livestock

Research shows that 25% of the flock carries 75% of the worms. With moderate exposure, many animals develop adequate immunity as they mature. Those that do not could be under-exposed, or deficient in immune function.

Varied sources of trace nutrients, such as biodiverse pastures and cafeteria-style minerals, can help animals fulfill individual needs. Excellent nutrition, low-stress environment and handling—and a good night’s sleep—all contribute to optimal immune function.

Excessive licking or rubbing, rough haircoat, poor appetite and weight loss can signal external parasites. Fly rubs, traps and vacuums have all been found to curtail fly populations when combined with other good management practices. An untreated back scratcher—a stiff brush attached to a pole—can significantly reduce lice.

Signs of internal parasites include poor haircoat, diarrhea, pale mucous membranes, reduced feed intake, weight loss, weakness and bottle jaw or pot belly. In many studies, bioactive plants, such as sericea lespedeza, birdsfoot trefoil, chicory and other tannic forages, were found to reduce fecal egg counts and clinical disease associated with gastrointestinal parasites in a variety of livestock species.

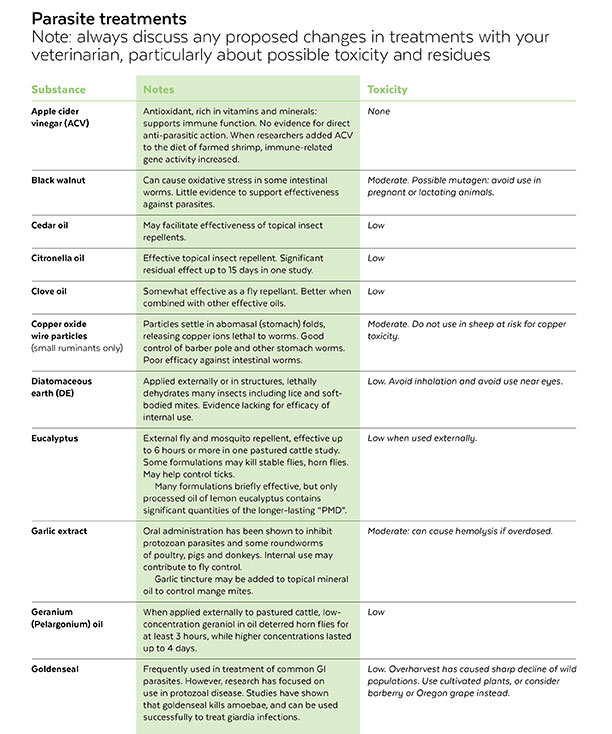

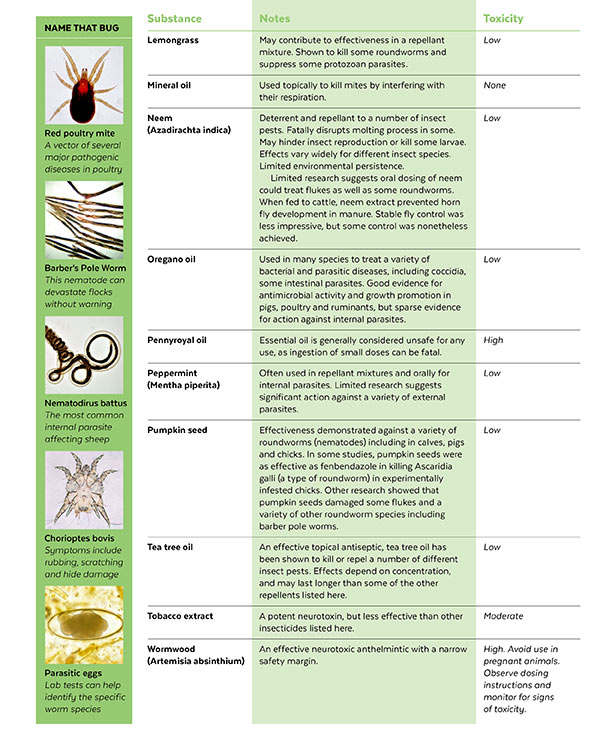

Treatments

The table (overleaf) describes several non-pharmaceutical substances commonly used to treat external and internal parasites. While some may be used alone, many are combined in spray-on, pour-on or oral formulations.

If parasites threaten animal welfare or farm viability, prompt, effective treatment is essential —and required under AGW’s standards. Treatment may include pharmaceutical parasiticides. Ivermectin has become the best-selling anti-parasitic; however, studies show that it is also toxic to dung beetle larvae and other beneficial organisms. Milbemycin is sometimes recommended as a less toxic alternative, although research also demonstrates negative effects on dung beetles and parasitic wasps.

The bigger picture

Effective management of parasites is essential for animal wellbeing and productivity. Ecological parasite management focuses on stewarding a functional agroecosystem where robust immune protection is facilitated by moderate exposure. Sustainable adaptation is slow process, but every step toward more ecological parasite management is a step toward a more resilient, more economical and less labor-intensive farm.

Essential Advice

- Treat individual animals as needed to ensure welfare and maintain economic viability.

- Manage pastures to maximize natural controls for the specific parasites present.

- Tailor fecal sampling to inform management decisions: pooled fecals reflect worm loads on pasture, while individual tests identify silent carriers.

- Record regular observations, including FAMACHA for small ruminants, to identify signs of infestation.

- Choose disease-free animals with low parasite burdens as breeders.

- Obtain treatments from reputable sources. Try to work with someone who has used a particular product successfully.

- Ask your vet to screen for interactions and residue risks, establish dosage, monitor for toxic effects, and determine triggers for switching treatments.

Author Jennifer L. Burton DVM is a veterinarian and educator with a special interest in the intersection of food animal medicine and public health.