One of the key attractions of our Certified Regenerative by AGW program is its practical…

Nature’s Efficiency

Abraham Lincoln once famously said that “Every blade of grass is a study, and to produce two, where there once was but one, is both a profit and a pleasure.”

And so it is at Tall Grass Bison. We manage our bison in socially structured extended family groups, which are so important to bison health and wellbeing. Our farm is a study in progress: we never stress the herd by breaking up families or ship them to a sale barn or packing plant. We never treat the animals with hormones or antibiotics or feed grain. We believe this approach—the harmony of nature’s animals and land—is not seen anywhere outside of Yellowstone National Park.

Natural order

Starting with three bison calves in 1976, we now maintain four to five extended families on converted crop ground and native oak savanna prairie. By managing herds for social order, we can obtain the unparalleled efficiency of nature and highest ethical animal care standards, all while maintaining a high level of ecological sustainability. And we believe it is possible to apply the principles of extended families and social order management to any domesticated grazing herd or flock animal.

Our beginnings at Tall Grass Bison started with growing up on a diversified Iowa farm, fortified with fish and wildlife biology degrees from Iowa State and Cornell University. College drilled into us that nature is most efficient. Yet modern agricultural practices said this wasn’t so. Where was the compatibility?

It took a career as a seasonal back country ranger in Yellowstone, for my part, to find solutions. For 30 years, I patrolled 1,200 square miles on horse, sometimes staying in for five months a year. While searching for poachers, this gave me the best possible opportunity to study wild bison and elk. It didn’t take long to see that these herds had a complex social infrastructure (families) only recognized before with elephants.

Observing nature

Combining these observations with an interest in indigenous people, I soon realized that the organization of hunter-gatherer communities and herd animals and flocks were the same; and how to manage and harvest herding animals became a lot easier to understand.

At Tall Grass Bison, we see our animals as owning the corporation, not us. It is the extended family that produces the product in the form of spin-off “satellite families,” which we then harvest as an entire unit. Our job is to make sure we don’t screw up and make the core families dysfunctional. As a result, our bison do not have the chronic stress and anxiety associated with intensively managed herd animals.

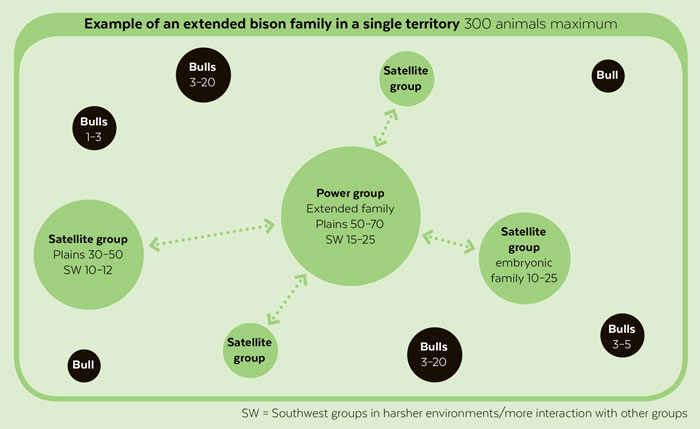

So, what do social order herds look like? Nature’s buffalo or cattle herds would consist of matriarchal core families of 60–70 animals (25–35 on arid lands) with great-great grandmothers down to dependent offspring. Spin-off satellite herds start with 20–25 animals. Bull groups consist of teenage (3–5-year-old) animals, active breeder age (6–8-year-old) of up to 15–20 animals and, finally, mentor grand-fathers in smaller groups of 3–5 in number. So, nature’s herds consist of maybe two-thirds matriarchal and one third males—like ours.

Around 300 animals seem to be the magical number for interactive recognition and association. It is the same for elephants, primates and elk. Beyond this number, the herd will split into territories, each protecting their turf from other herds. Although recognition and support continue between distantly related groups, the relationship becomes more about common cause, trust and familiarity rather than emotional attachment.

The advantages?

In modern husbandry a dry cow is considered a burden to the rancher’s bottom line and is slaughtered after pregnancy checking. In social structured herds, however, a dry cow becomes the babysitter for other calves so the mother can forage better. She gathers up all the stragglers when the main herd goes to pastures across the road. There is no panic when mothers see their calves are not with the herd. They can watch over older dependents while the babysitter (who may be the grandma) does a quick survey to see who is missing, walks back, and returns later with the missing youngsters.

As for the males, we used to park our John Deere 3020 in front of the field gates when it was moving time to keep the crunch of the herd from breaking through. After 10-12 years, the older bulls have assumed herd discipline. Now, one or two walk to the front, turn sideways, and the rest of the herd stays back. Even after the gates are opened there is no movement until those bulls turn parallel to the lane. Then everyone rushes past them to get to new grass on the other side of the road. These non-breeding bulls and old cows are therefore worth a lot in terms of overall herd performance.

Grazing

Susan and I are part of Utah State University’s Behavioral Education for Human, Animal, Vegetation & Ecosystem Management (BEHAVE) initiative. Members discuss such topics as “eating the best and leaving the rest,” riparian overgrazing problems and fencing needs for rotational grazing. But with social order herds the solutions usually happen naturally.

Because grazing families stay close together, we end up with multiple families practicing management intensive grazing (MIG) without fences at different locations in the same pasture. With families there are two types of grazing: en masse movement and static.

With en masse grazing, yearlings and two-year-old dependents lead the herd, staying just in front of their older relatives. They eat the most succulent forage (eliminating conventional creep feeding) and keep the entire herd moving forward for more uniform grazing across the landscape. Add in nature’s usual male component within the herd and you now have a group that utilizes coarse vegetation, resulting in new growth for females and dependents without the cost of brushing pastures.

During times of static grazing the young learn what to eat from their elders. With most native forbs (and weeds) that means not eating from the top down, but rather selecting out high nutrition parts of the plant at appropriate times of the year. Without this training, herbivores are relegated to a nutrient-deficient “grassivore” existence.

Herd development

It takes 12-15 years to establish a basic, functional social order herd in cattle or buffalo (less time with pigs, goats and sheep). This may seem like a long time but it is no different than the time required for a purebred beef producer to establish his or her own line or distinctive herd identity.

In social order herds, the cows of each functional family pick the males to mate with. Thus, grandma, mother and daughter can have offspring from the same male without inbreeding. The younger, unrelated bull who always follows this older male mentor around will breed with the younger females after the old guy is exhausted from mating with the older cows. With separate family identity, herds with multiple families can therefore offer a closed, disease-free option for producers. Finally, only in extended families does one have a situation where every animal in this family can pass on genes without necessarily having offspring. I suspect farmers and ranchers reading this article can figure this one out better than most of the animal scientists presented with this concept!

The final product

We field slaughter all members of a family, leaving other families structurally intact. This means harvesting every animal in a matriarchal family—from calves to 25-year-old bulls and cows—and can include up to 150 individuals per harvest. The male components are also harvested as entire bull groups. And there are always individuals to harvest who are shunned by their families. If this seems counterproductive, think about having three towns: is it better to disrupt the infrastructure of all three or to eliminate one and leave the other two to absorb the resources of the third?

In the last year we sold $160,000 worth of half quarters, quarters and hanging halves to private customers across the U.S. We match the meat from every age of animal with the ages and activity levels of our customers, on the basis that softer muscle of very young and elderly animals is easier to digest for preschoolers and seniors. Active-aged humans need the superior nutrition offered by the meat of mature animals (remember that an animal cannot concentrate nutrients until growth stops). Finally, it is a myth to assume that the meat from mature animals is tougher. Without the chronic stress associated with dysfunctional, weaned animals, muscles don’t get tight and acids don’t build up.

Animal welfare

It is impossible to raise herd animals in families without acknowledging that we are their brother’s keepers. One learns, therefore, to be sensitive not only to each individual, but also to the whole family. This includes putting hay out in the winter in different locations for each family. And you soon learn that you cannot shoot or field slaughter individual animals in a herd and still expect to get fresh, clean tasting, tender meat from the rest!

There are many other topics that we don’t have space here to cover, such as the importance of families in predator defense, the cascade effect on other species, and the fact that, in terms of ecological sustainability, nothing in modern management even comes close. I look forward to sharing our experiences in the future.

Gregarious herds and flocks, such as bison, elk and geese, are actually made up of multiple core and extended family units.

In bison, the most visible and pertinent family grouping applicable to private producers is the extended family – or grazing grouping. It consists of related lead cows and as many of their adult female offspring (and their juvenile offspring) as they can control, teach and care for. The more fertile the ground, the stronger and larger this family can be. In the 50,000 or so miles I have ridden horseback in the mountains of Yellowstone, the largest family unit seen was around 60 bison. When the herd gets bigger than 60 or so, satellite herds spin off. They are still dependent but keep varying distances apart from the core group. Once numbers of all related groups get to 300 (bull groups included) or so territories are formed and competition between herds from different territories commences.

I say pertinent family grouping because most basic life needs depend on this unit. Without this grouping, bison could not exist as a species in the wild. It is responsible for dispersal grazing, dissipation of inappropriate behavior, social order and even prevention of inbreeding. With bulls breeding from 6–8 years of age, and all breeding age individuals (three years of age and older) of matriarchal groups being related, one gets line breeding without inbreeding. It is the perfect combination for the survival of the best characteristics and the reason all ungulates got to where they are today. Human manipulation of animal breeding doesn’t come close and is not sustainable. Everything, everything depends on this basic structure.

If we can only understand how bison choose to live, and maintain respect for them, then there will be no abuse. It will be good for the bison and good for the industry as well.

Bob, Susan and Scott Jackson of Tall Grass Bison manage more than 400 grassfed bison on 1,000 acres near Promise City, Iowa. Visit tallgrassbison.com